|

The Blue-eyed Scallop

The Atlantic Bay

Scallop , also named the Blue-eyed Scallop is a

"Molluscan maverick". The species has succeeded

by breaking or bending the rules of "bivalvery"

at almost every turn.

The shells are identical

(actually mirror images of one another) except

for the color. The top shell is darker,

often with bands of alternating brown and cream.

The bottom shell is white. Both shells are

strongly ribbed, with up to twenty raised lines

radiating from the base. Scallops cannot dig as

clams do, so the dark top shell helps it to

camouflage as it sits on the dark, muddy bottom.

Weeds and sponges grow on it as well,

completing its disguise.

Scallops spend most of

their time resting on the sea floor with their

shells slightly open to feed. They are filter

feeders and catch their food by pumping water in

through the front of the shell and out through

the back. Any food particles, such as small

bits of algae, diatoms, and bacteria, are

trapped inside.

The shells are more

lightweight than clams or oysters, and the

reason for this is that the scallop is one of

the few type of bivalve the Northeastern

Atlantic region that can actually swim.

Tiny yellow hair-like projections stick out between the shells when the

animal is at rest. These are sensitive to

chemicals in the water. When they sense a

predator, such as a sea star, the scallop opens

its shells wide, drawing in water, then clamps

the shells quickly shut. As the shell closes,

the mantle, which is a thin sheet-like organ

that actually creates the shell, seals the

opening. This forces all of the water to shoot

out through the back hinges of the shells,

moving it forward through the water, and away

from the predator, via jet propulsion.

Scallops swim in a zigzag

motion with the rounded part of the body forward

and occasionally bounce off the bay bottom.

Swimming can last anywhere

from a few seconds to a couple of minutes,

depending on water currents and the severity of

the threat. A potential predator that the

scallop perceives as more of an annoyance, such

as a sea urchin, may cause the scallop to just

give itself a short, quick burst to move it away

from the danger. The scent of a sea star,

probably the deadliest predator an adult scallop

is likely to face, will cause it to go ballistic

as it desperately tries to put as much distance

between itself and the enemy as possible.

Scallop

swimming video

<click here>

The decision to swim away

from a predator or close its shells tightly

depends on the type of predator that is near it.

If the predator sensed is able to open the

shell, the swimming defense kicks in. If the

predator cannot then the scallop simply seals

its shells up until the danger passes.

A bivalve's strength comes

from muscles called adductors. Most have two, and these work

together to clamp the shells tightly shut. To

open the shells slightly, as they do when

feeding, these muscles are simply relaxed a bit.

The Bay Scallops only have

one, but it is a whopper. This is where the

power comes from which allows this animal to

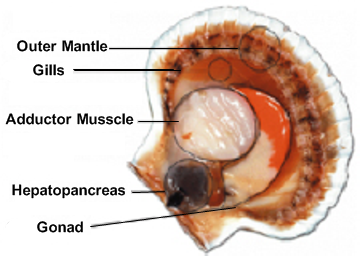

swim. In the diagram to the right, (courtesy of

www.food.gov.uk) you can see the enormous

size of this muscle, as well as some of the

other anatomical features. Notice especially

the size of the gonads.

Scallops are

hermaphrodites. Each animal is both male and

female, although they do not self-fertilize (the

sex cells of each individual mature at different

rates). When the gonads are fully formed they

are simply released into the water column to mix

by chance with that of other individuals. Water

temperature cues trigger the release so that all

gravid scallops in an area spawn at the same

time. This greatly increases the odds that the

eggs will be fertilized, and scallops have only

one chance at this so they need to make it

count. All bay scallops spawn when they are two

years old. Then they die.

Larval scallops are

planktonic and in a few days they will form a

rudimentary shell (this stage is called a

"spat") and settle to the bottom to grow.

However there is a catch. Scallops live in

muddy bays and harbors and a tiny spat that

lands on the mud will suffocate from the silt.

The larva must find something suspended above

the mud to hang on to until it is big enough to

resist being silted to death. Eelgrass is the

predominant plant (and it is a true plant) in

scallop habitats and is a vitally important

substrate for the young mollusk to attach itself

to. Larval scallops are

planktonic and in a few days they will form a

rudimentary shell (this stage is called a

"spat") and settle to the bottom to grow.

However there is a catch. Scallops live in

muddy bays and harbors and a tiny spat that

lands on the mud will suffocate from the silt.

The larva must find something suspended above

the mud to hang on to until it is big enough to

resist being silted to death. Eelgrass is the

predominant plant (and it is a true plant) in

scallop habitats and is a vitally important

substrate for the young mollusk to attach itself

to.

Like mussels, scallops can

produce byssal threads using a small gland at

the base of the shell. The spat uses these

thin, sticky threads to hold on to the blade of

the plant. Adults also can produce

byssus and

the threads, when the scallop needs to swim, can

be instantly snapped at will.

During the 1930's a fungus

known as "eelgrass blight" decimated the plant

all along the Atlantic coast. It took decades

for the grass beds to recover. During these

years the scallop fishery literally vanished.

Now,

about those eyes. When the scallop's shell is

gaped you can see two rows of tiny, bright

blue

eyes. This species has forty of them. And

these aren't the simple light sensitive eyes

that most mollusks have (discounting, of course,

the incredible sight possessed by cephalopods).

They can also sense motion, so a crab or fish

trying to sneak up on one and grab some flesh

before the shells close will be seen before it

gets even close. And if the scallop loses an

eye it simply regenerates a new one in its

place. blue

eyes. This species has forty of them. And

these aren't the simple light sensitive eyes

that most mollusks have (discounting, of course,

the incredible sight possessed by cephalopods).

They can also sense motion, so a crab or fish

trying to sneak up on one and grab some flesh

before the shells close will be seen before it

gets even close. And if the scallop loses an

eye it simply regenerates a new one in its

place.

To the right is an ultra close-up of the eye.

(The color hasn't been tampered with)

|